During the final weekend of November the dog and I were back at Fishmore Hall near Ludlow. In theory we were there to enjoy the Medieval Fayre which was set up in the grounds of Ludlow Castle but one of those named storms had struck the night before it was due to open and wrecked everything and the event had to be cancelled though a band of medieval-style musicians braved the winds and played music in the Market square, partying like it was 1399. In one respect, we got off lightly as, at the same time, much of the West Midlands had a vast amount of snow dumped on it by the Great Weather God.

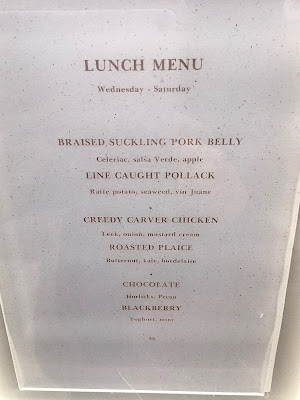

The weekend at least gave me an opportunity to witness how Forelles (Michelin plated) restaurant at Fishmore was faring under the rule of its new Head Chef, Phil Kerry (see Blog175). As well as eating in the ‘Bistro’, I had dinner and Sunday lunch in Forelles.

First, Sunday lunch. An excellent starter of pleasingly mildly flavoured smoked mackerel rillette complemented very nicely by pickled cucumber with avocado purée and a little sprinkle of caviar. A fine-looking (and tasting) dish whose elegance was lost by the mildly ungainly positioning of a chunk of toasted bread on the side of the plate. Rustic in appearance also was the main course.

I chose roast leg of lamb which was very tender but extremely subtley flavoured to the extent that it was completely overwhelmed by a powerfully tasting cauliflower cheese which might have been good as a dish in its own right but which dominated the roast lamb to the point of extinguishing any of the lamb’s flavour. Other accompanying vegetables also piled the pressure on the unfortunate lamb - the red cabbage, again very good in itself, negated the flavour of the lamb. The roast potatoes were very good with some nice crispiness and the mashed swede was pleasing but the mint sauce was very sugary and needed much more acidity. Hmmm … a curate’s egg I think. I think all these accompanying vegetables would have worked very nicely with robust roast beef or pork which were on offer but some thinking is needed as to what is appropriate to be served along with the delicate lamb.

I thoroughly enjoyed an elegant dessert of excellent vanilla panna cotta served with a delicious strawberry and vanilla shortbread.

The previous evening I had had dinner in Forelles. I chose the à la carte menu but my appetite was such that I could only manage just two courses (though they came along with an enjoyable amuse gueule, bread and predessert). For the main course I chose a beautifully cooked piece of stone bass with a delightful crispy skin, one of my favourite fish dishes, accompanied by some very nicely textured samphire (though it had less flavour than I might have been expecting), a mesmerisingly delicious crab croquette, perfectly cooked chard, pumpkin and a beurre blanc. This was a very fine dish indeed.

I rounded off with what is one of Forelles’ signature dishes, featured in previous Blogs, the immensely enjoyable baked Alaska which quite rightly seems unmutated, unlike the wretched coronavirus, since it was first delivered to an expectant table at Forelles. Little happinesses!

With the Medieval Fayre cancelled, Lucy and I walked around Ludlow town spending far too much on books in the excellent little independent bookshop in the market square. I found a paperback copy of Jane Gregson’s English Food of which more in the next paragraph. We walked past the butchers shop of DW Wall and Son and photographed the virtual flock of pheasants hanging outside waiting to be snapped up by lucky local pheasant eaters. It rather begged the question as to why local eateries are not offering the bird on their menus. Perhaps some are, I haven’t looked at the menus of all the fine local restaurants. How wonderful it would be to be able to capture such a picture in Birmingham.

I enjoyed perusing Grigson’s book mentioned above which was published first in 1974. The introduction is as pertinent now as it was then, “….There’s an extra special confusion nowadays in talking of good and bad national cooking. The plain fact is that much commercial cooking is bad, or mediocre in any country - it’s easy enough to get a thoroughly disappointing meal even in France where there exists an almost sacred devotion to kitchen and table. The food we get publicly in England isn’t so often bad English cooking as a pretentious and inferior imitation of French cooking or Italian cooking”.

Grigson’s observations were so spot on. What we eat today, and what smart people ate then, are direct consequences of post-war food history and a few events which happened but might just as easily not have happened. British food doubtlessly deserved a poor reputation during the period of socialist austerity inflicted on the nation by Attlee’s government, viewed now through rose-coloured spectacles by the reconstructors of modern British history, which inflicted years of unnecessary post-war food rationing from the mid-1940s to the early 1950s on the people who at times were half-starved. You can’t have a brilliant cuisine if the ingredients you have available to make a meal are not available.

And then rationing ended and people had the ingredients once more but not the experience of cooking them. Boiling, roasting, frying - frequently, if not universally, to the point of near-cremation or disintegration. Along came Elizabeth David, the only British food expert to be featured on a British postage stamp, who, having lived in the sunny Mediterranean area, bemoaned grey post-war and post-socialist Britishness, especially in food, and brought in, for better or worse, the concept that Mediterranean food, Italian or French, was infinitely superior to anything the English could cook up. Suddenly there was a national craving for spaghetti with many being hoodwinked by the perfidious BBC, ever mischievous, into believing that spaghetti grew on trees and was harvested by Italian peasants.

Of course, more than half a century before L’Escoffier, with French arrogance, had been plying his trade at the Ritz convincing everyone that French cuisine was the pinnacle of gastronomy and that various sauces with ridiculous names were the must-eat way to dine. The English swallowed this hook, line and sinker and if for no other reason than snobbery, embraced French cuisine with ardour. This conviction that French cuisine was best stayed with them over the coming years and Elizabeth David ensured this postwar culinary Francophilia continued to hold on through the age of never having it so good, of the white heat of technology and the sordidness of the later sixties.

And then the Roux brothers came to London and French cuisine dug itself in for the coming years. Michelin deigned to recommence publication of its Great Britain Guide in 1974, and for a long time the only chance a restaurant had of being included in the book was to serve French cuisine. Then Italian cuisine became highly fashionable and Birmingham began to get a mention in the Michelin Guide while scattered restaurants in small towns or rural locations in the West Midlands counties even gained the occasional star though they too usually offered French cuisine.

We have travelled through various fashions from nouvelle cuisine to modern British with Japanese twists but French cuisine has always been wallowing in the mud at the bottom of the menu and high prices are no guarantee that, as Grigson wrote, it has been done well. How wonderful it would be to have a local restaurant which does fine dining traditional English dishes - and I don’t mean that it just does expensive, pretty, tiny pies (not pithiviers please) or micro-slivers of high quality English beef (not called Wagyu please) with a cubic centimetre of tarted-up batter calling itself Yorkshire pudding.

Grigson’s book looks rather promising and I think I shall devour it (but not literally of course).

I completed my stay in Ludlow with a visit to the Assembly Rooms to listen to a concert of mostly traditional English folk music by the master fiddler of our time, Sam Sweeney. Traditional English food/traditional English folk music - so much to feel happy about even as omicron comes bubbling up to the surface.