The Main course and Dessert course (not to mention Pre-dessert) heat of the Central Region in the BBC’s Great British Menu which was broadcast on 25 March and which was contested with passion and pride for the region and ended with Stuart Collins of Docket No.33 in Whitchurch and Sabrina Gidda, originally from Wolverhampton but working in London, going through to the region final. Gidda beat Liam Dillon of The Boat Inn near Lichfield by a single point but as it was her third attempt, and the programme makers seem to dislike potentially humiliating a chef by turning them into a three time loser, the outcome of this particular heat was perhaps not particularly surprising. What was clear was that Collins goes into the final as clear favourite.

Continuing the theme of celebrating British innovators and inventors, Liam Dillon produced a main course using Cannock Chase venison in what at least looked like a rather alluring Wellington calling the dish “Oh no my deer” for which he scored 7 points. The dish celebrated the Nobel Award winning great British scientist Dorothy Hodgkin whose work with crystallography advanced medical knowledge significantly. Surprisingly, I think, Dillon did not make his own pastry and that surely must have counted against him.

Sabrina Gidda’s main course was titled “Everything goes with brown sauce” and celebrated the invention by Frederick Gibson Garton in Basford in Nottingham of brown sauce and it’s one time production at the HP Sauce factory in Aston in Birmingham till it was egregiously stolen away. The dish was based on a masala tenderloin of pork with an additional Black Country faggot and Gidda substituted brown sauce as an ingredient for whenever she would have used tamarind. One of the most enjoyable outcomes of the idea was that when, during the course of the programme, Gidda asked the other chefs if they would have brown sauce or tomato ketchup with their breakfast and Collins suggested that he would choose to have ketchup with bacon and brown sauce with sausages, a choice which Dillon endorsed. An interesting question for any chef with a chef’s taste and I’m not clear what the logic behind the choice is but Gidda looked somewhat shocked at the answers and clearly thinks brown sauce would have been the correct choice for both. I agree entirely with her, I have never been a fan of tomato ketchup, and head straight for the brown sauce bottle though I shun HP Sauce (all the more reason to do so now it’s not made locally) and instead opt for Branson Fruity Sauce, a condiment of great pleasure, which is not being as disloyal to the West Midlands as one may think as it is made in Branston in Staffordshire. So that’s alright then. Gidda scored 9 points for her main course.

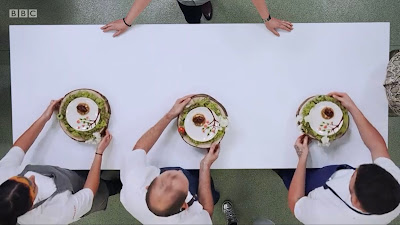

Collins’ main course was “Dissected Maps” which celebrated John Spilsbury of Worcestershire who invented the jigsaw 200 years ago. The dish was aimed at highlighting superb Midlands produce cooked to perfection and was centred on rose veal raised in Uttoxeter in Staffordshire using prime cut and shin. The flavours were heightened by an onion and beer purée. The whole was served on a jigsaw made up of some of the counties of the West Midlands with each part of the overall dish placed on the county where the ingredient had originated. It received 8 points and was described as “well-executed” but lacked a little in the excitement that one might expect to be served at the banquet though if served in his restaurant it would have been wonderful.

The pre-dessert course was actually won by Liam Dillon with an amusing little offering “The Jigsaw” also referring to Spilsbury’s invention and then on to the dessert course itself.

Liam Dillon commemorated Dr Samuel Johnson - the producer of a great English dictionary - who hailed from Lichfield with a dish titled “How do you spell that?”. It was a lovely-looking dessert - a layered cake with the first layer being a coffee-soaked sponge, then chocolate ganache though Dillon hesitated to use the French word “ganache” as Dr Johnson had disliked the French so much, white chocolate mousse, another layer of ganache tactfully called “chocolate glaze”, topped by edible “texts” from Johnson’s dictionary and tuiles. The dish was eventually awarded 7 points.

Stuart Collins’ dessert was another layered chocolate cake named “Radcliffe Road” which commemorated the first tarmac-surfaced road in the world - Radcliffe Road in Nottingham, tarmac having been patented in 1902 by Edgar Hooley, a Welshman who was a surveyor in Nottinghamshire. The cake included in its layers Earl Grey jelly and a chocolate and nougatine mousse. At the judging the dish was awarded 9 points.

Sabrina Gidda’s dessert commemorated Birmingham-based chemist Alfred Bird’s invention in 1837 of artificial egg which he was moved to do because his wife had an allergy to egg. Subsequently his invention was used in the manufacture of custard in Birmingham for many years. The dessert was made up of an egg-free custard tart, the base of which was egg-free shortcrust pastry served with an egg-free custard ice cream. In the judging Lisa Goodwin Allen felt that the ice cream was too rich with a powdery aftertaste and she said that the icecream, “wasn’t pleasant” with the dish requiring “more refinement”. She awarded the dish 6 points but this gave Gidda one point more than Dillon in the final overall score so she and Collins were put forward to the regional finals. Exciting or what? By the way I’ve made a reservation at Docket No. 33 for later in the year, Boris permitting.